The Royal Łazienki Museum in Warsaw has received an anonymous package from Canada containing 12 Dutch tiles from the 17th century that were lost during World War II. These recovered tiles are now showcased in a temporary exhibition at the museum.

The Royal Łazienki Museum in Warsaw, celebrated for its historic park and palace complex, recently received an extraordinary anonymous parcel from Canada. Inside the package were 12 Dutch tiles from the late 17th century, which originally adorned the museum’s bathing pavilion before vanishing during the Second World War.

These tiles were integral to the elaborate decor of the bathing pavilion at the Royal Łazienki Museum, a site of considerable cultural and historical importance in Poland’s capital. They disappeared during World War II when Nazi forces plundered the country.

Poland’s Ministry of Culture shared the news on Facebook on April 26, stating, “A mysterious package, missing tiles and a happy ending. This story is a ready-made script for a movie! After many years, the original Dutch ceramic tiles that decorated the interior of today’s Palace on the Isle are returning to the Royal Łazienki Museum. Some of them survived the fire of the Palace in 1944, some were scattered, and the missing ones were reconstructed after the war. Unexpectedly, after many years, the museum received a shipment of original tiles from a mysterious sender from Canada who, just before his death, asked for their return.”

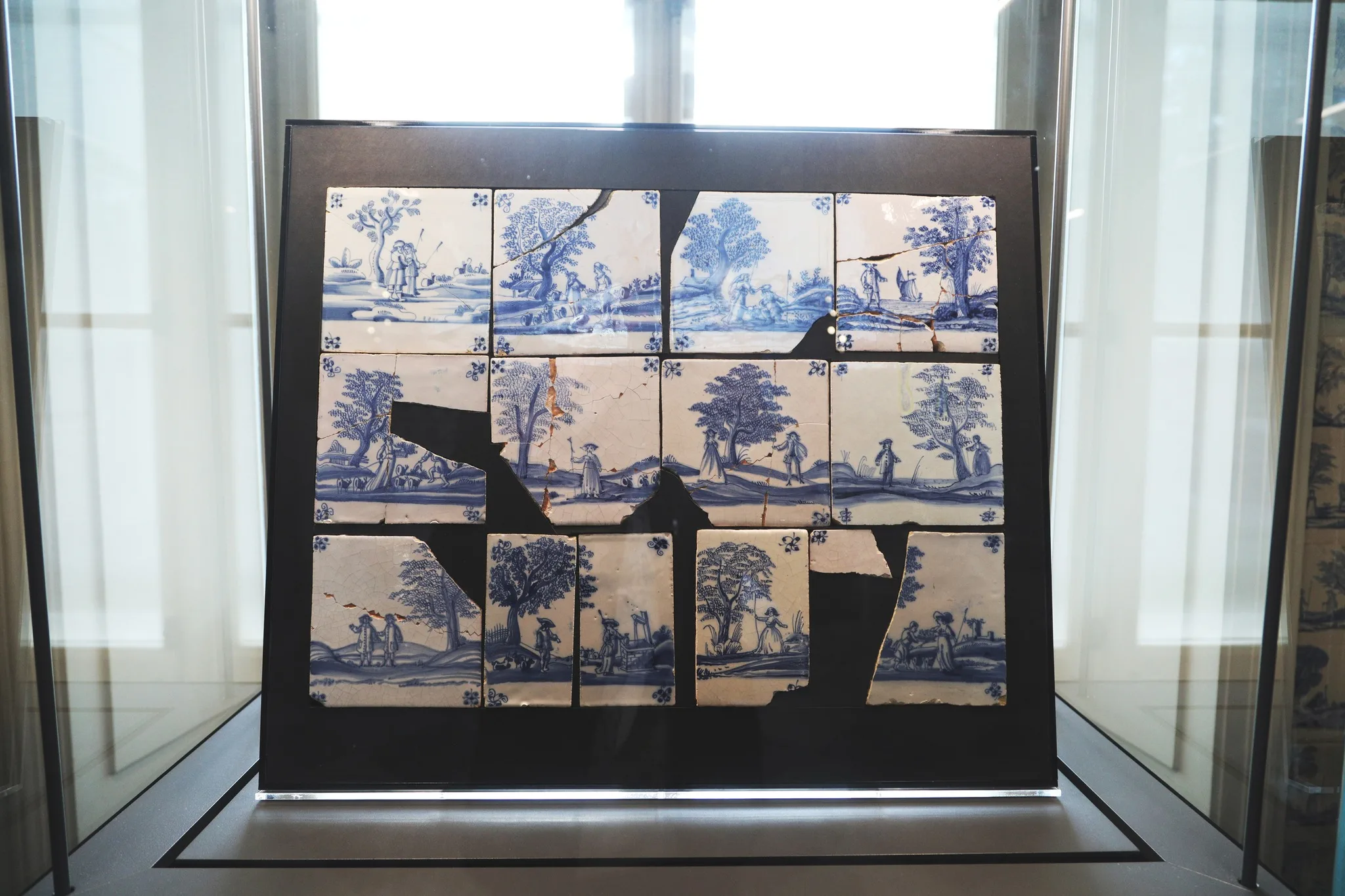

The condition of the returned tiles is fairly good with some cracks and missing pieces. They are presently on display until September 1 in a temporary exhibition titled “The Art of Thinking Well. The Legacy of Stanisław Herakliusz Lubomirski.” This exhibition pays tribute to the Polish nobleman and intellectual who founded the estate. The bathing pavilion, initially constructed in the 17th century, gained renown when King Stanisław August expanded it, converting it into the Baroque Baths Palace or Palace on the Isle.

A museum spokesperson stated that the tiles, dating from approximately 1690-1700 and probably made in Utrecht, “were sent to us just before the exhibition” and “hold great significance for us, as they are the original tiles that once decorated the walls of one of the rooms in the Palace on the Isle.”

The story highlights the often lengthy journey, sometimes spanning decades, that wartime stolen art takes to be returned home.