Ancient tablets acquired by the British Museum decades ago have recently been deciphered, revealing unsettling insights into the way Babylonian kings interpreted celestial events. A team of researchers has successfully translated 4,000-year-old Babylonian cuneiform tablets that had remained untranslated for over a century.

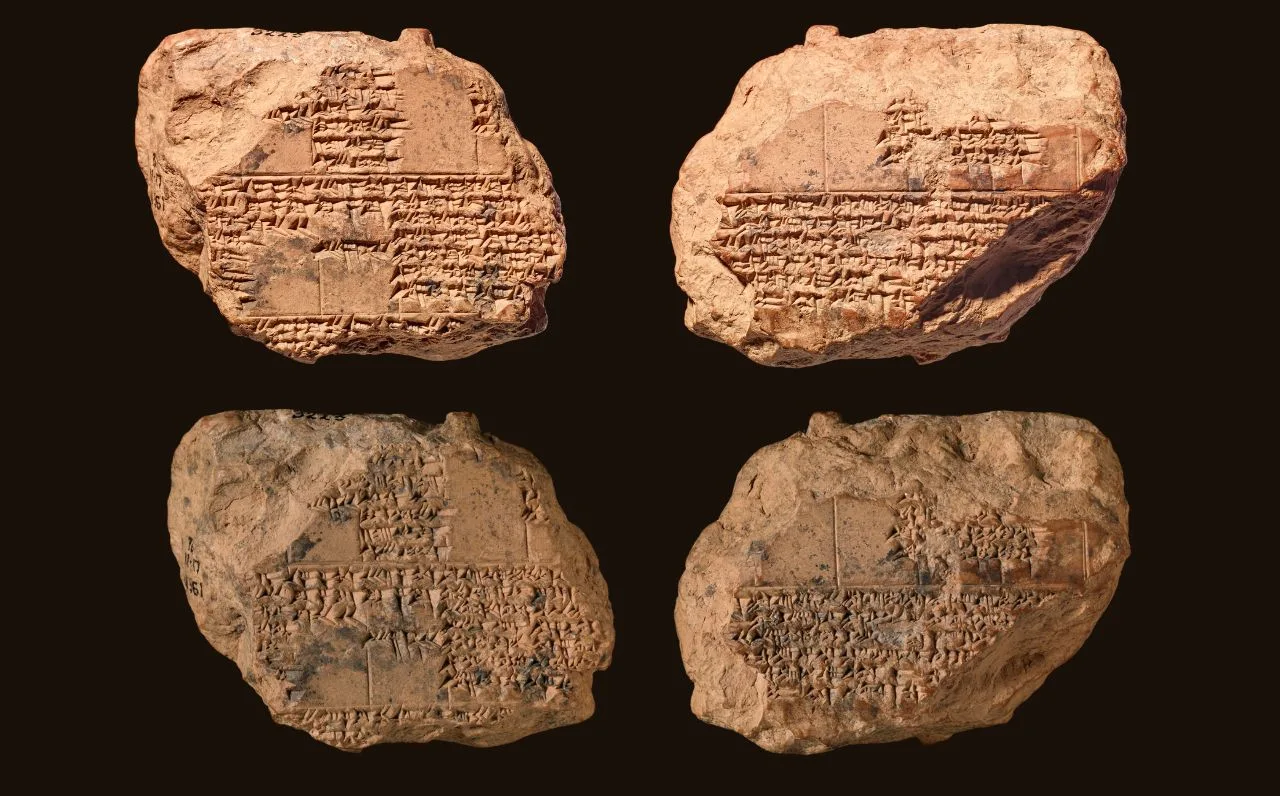

The recent research focused on four tablets from the British Museum’s collection, dating back to approximately 1200 BC from the ancient city of Sippar, located in present-day Iraq. The results of the study were published in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies. These newly deciphered texts reveal that the Babylonians regarded lunar eclipses not merely as astronomical phenomena but as ominous signs of impending doom and disaster.

One of the tablets ominously notes that “an eclipse in the morning watch” signifies “the end of a dynasty.” Another tablet issues a dire warning: “If an eclipse becomes obscured from its centre all at once and clear all at once: a king will die, destruction of Elam.”

These inscriptions were authored by astrologers of the Mesopotamian civilization, and now represent the oldest known records of lunar eclipse omens.

According to the researchers, “Omens arising from lunar eclipses were of great importance for good statecraft and well-counseled government.” The paper further explains that in later periods, astrological observations became integral to protecting the king and ensuring that his actions were in harmony with the will of the gods.

Fortunately for these ancient rulers, there were measures available to counter such ominous predictions. These included consulting oracles, who would examine animal entrails, and performing prescribed rituals to mitigate the perceived dangers.

The Babylonians

The Babylonians were an ancient Akkadian-speaking civilization that thrived in Mesopotamia, the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq and parts of Syria and Iran. Their influence on human history is profound, with significant contributions to science, agriculture, literature, and law. Notably, their base-60 number system is still used today in the measurement of time and angles, and they produced some of the earliest known literature, including the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Initially a modest city-state in the late third millennium BCE, Babylon rose to prominence under the rule of King Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 BCE). Hammurabi’s code of laws, inscribed on a large stone stele, is one of the earliest and most complete legal codes in history.

Hammurabi Code comprises 282 laws, each outlining specific punishments for various offences. For example:

– Law 21: “If anyone breaks a hole into a house (break in to steal), he shall be put to death before that hole and be buried.”

– Law 157: “If anyone be guilty of incest with his mother after his father, both shall be burned.”

– Law 196: “If a man destroys the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye. If one breaks a man’s bone, they shall break his bone.”

One of the most legendary features of Babylon was the Hanging Gardens, often cited as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was believed to be located near the royal palace in Babylon. The gardens were described as an engineering marvel, featuring an ascending series of tiered gardens containing a wide variety of trees and vines. Tradition holds that these gardens were either created by Queen Sammu-Ramat, who ruled from 810 to 783 BCE or commissioned by King Nebuchadnezzar II to console his wife, Amytis, who longed for the mountains of her homeland.

However, despite extensive archaeological efforts in Babylon and the surrounding areas, definitive evidence of the Hanging Gardens has yet to be found, leading many to speculate that they may be a creation of myth.