A recent study published in Nature has genetically traced the origins of the Indo-European language family, which comprises over 400 languages spoken by more than 40 per cent of the global population today.

Professor Ron Pinhasi and his research team from the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at the University of Vienna, in collaboration with David Reich’s ancient DNA laboratory at Harvard University, have made significant advancements in understanding the emergence of Indo-European languages. Their study analysed ancient DNA from 435 individuals excavated from archaeological sites across Eurasia, dating from 6400 to 2000 BCE. The findings reveal a previously unrecognised Caucasus-Lower Volga (CLV) population linked to all Indo-European-speaking groups.

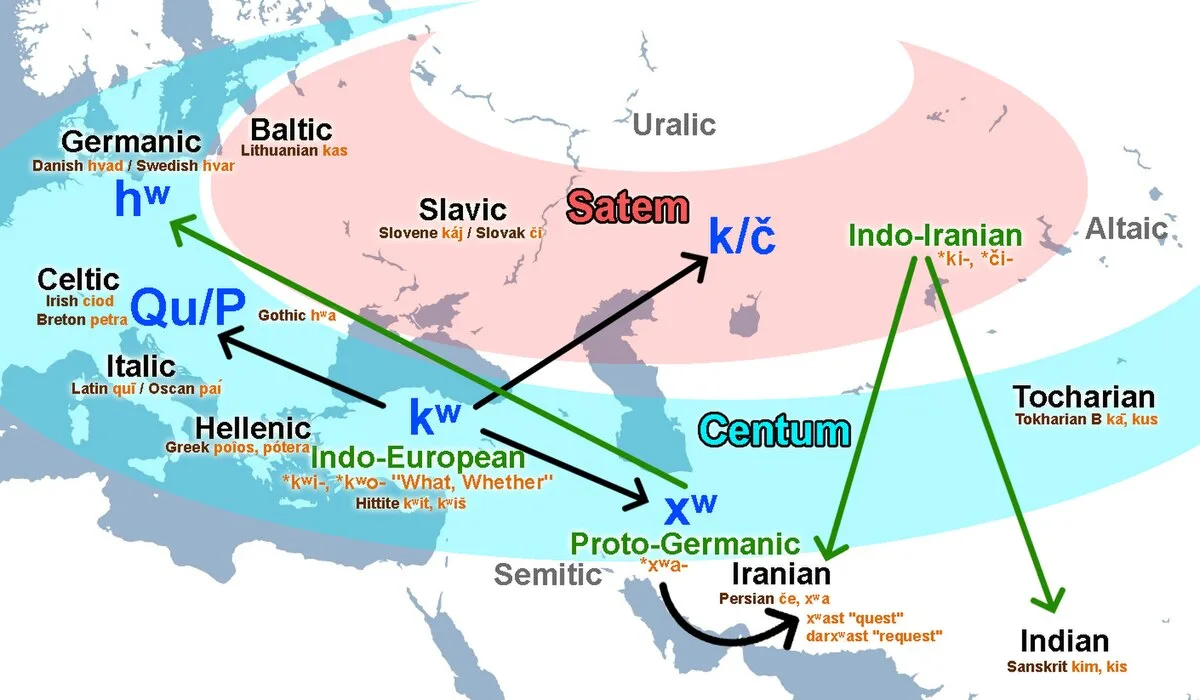

The Indo-European (IE) language family encompasses several major branches, including Germanic, Romance, Slavic, Indo-Iranian, and Celtic, and originates from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language. While historians and linguists have long sought to determine its origins and dispersal, significant gaps in knowledge have persisted.

The latest study, which also involved Tom Higham and Olivia Cheronet from the University of Vienna, builds upon earlier genetic research identifying the Yamnaya culture (3300–2600 BCE) of the Pontic-Caspian steppe as a key migratory force into both Europe and Central Asia from approximately 3100 BCE. This migration is considered to have had the most substantial impact on European genomes over the past 5,000 years and is widely regarded as a principal factor in the spread of Indo-European languages.

Historically, the Anatolian branch of Indo-European languages, including Hittite, was the only group that did not exhibit steppe ancestry. Hittite, believed to be the oldest branch to have diverged, retains linguistic features that have been lost in other branches. Senior author Professor David Reich of Harvard Medical School and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences explained, “We know from cuneiform tablets that the Hittites spoke Anatolian, yet they did not possess Yamnaya ancestry. We conducted an extensive analysis but found no evidence of it. This led us to hypothesise that an earlier population must have been the true source of Indo-European languages.”

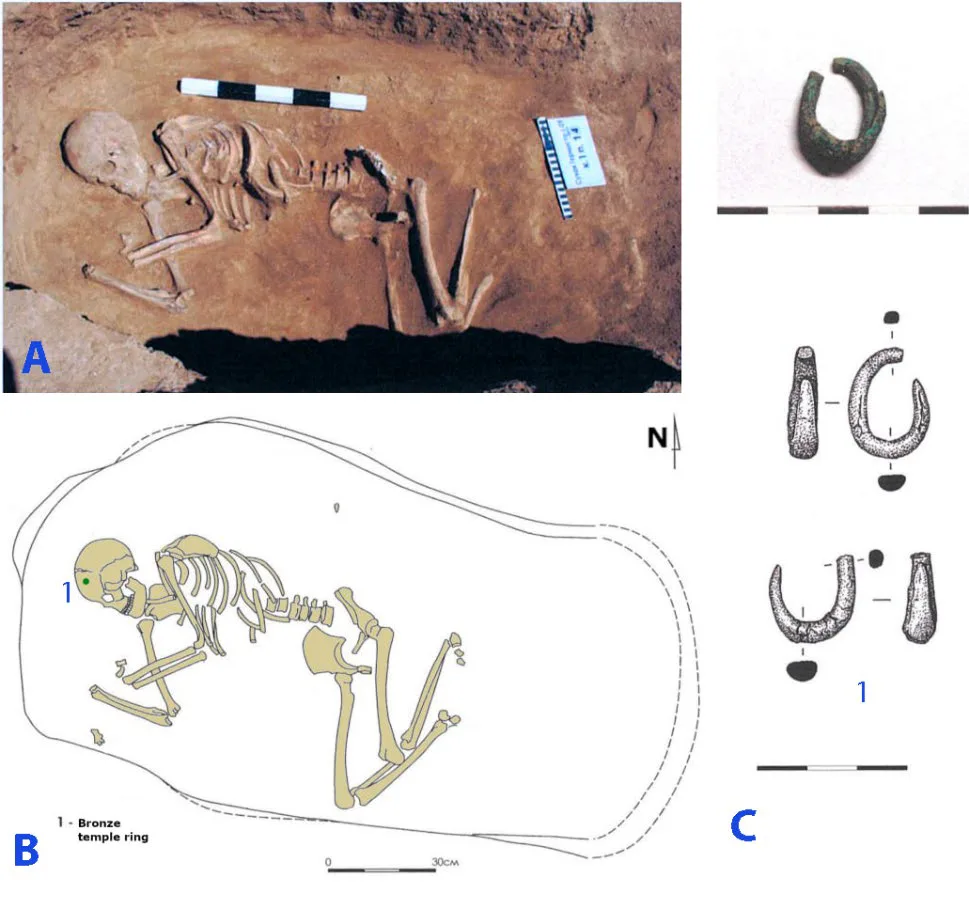

Previous studies failed to detect steppe ancestry among the Hittites, but this new research suggests that Anatolian languages originated from a population that had not been adequately characterised before. This group, an Eneolithic population dating from 4500 to 3500 BCE, resided in the steppes between the North Caucasus Mountains and the lower Volga. Genetic analysis indicates that at least five individuals from Anatolia, dating to or before the Hittite era, exhibited CLV ancestry.

The research further reveals that the Yamnaya population derived approximately 80 per cent of its ancestry from the CLV group, which also contributed at least 10 per cent of the genetic heritage of Bronze Age central Anatolians, who were speakers of Hittite. This finding suggests that the CLV people were the original source of these linguistic lineages, establishing a newly uncovered connection between the Yamnaya and the ancient Indo-Anatolian speakers who once inhabited parts of present-day Turkey.

Professor Ron Pinhasi elaborated, “The CLV group can be linked to all Indo-European-speaking populations and is the most likely candidate for the people who spoke Indo-Anatolian, the ancestor of both Hittite and all subsequent Indo-European languages.” The study further suggests that the integration of the proto-Indo-Anatolian language reached its peak within CLV communities between 4400 and 4000 BCE.

“The discovery of the CLV population as the missing link in the Indo-European story marks a pivotal moment in the 200-year endeavour to reconstruct the origins of the Indo-European people and the pathways by which they spread across Europe and parts of Asia,” concluded Professor Pinhasi.

Co-lead author Iosif Lazaridis, a research associate in Human Evolutionary Biology, remarked, “For the first time, we have a genetic framework that unifies all Indo-European languages.”

This discovery represents a milestone in the long-standing quest to trace the roots and migrations of Indo-European speakers across Europe and Asia. With this new genetic evidence, researchers are now better equipped to explore the intricate tapestry of human history and the profound interconnections that have shaped linguistic evolution.