After the recent terror attacks in Pahalgam, Kashmir, the Indian government has decided to revoke its longstanding Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan. But what is the Indus Water Treaty?

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was signed on 19 September 1960 and entered into force on 1 January 1961. It stands as a landmark agreement between India and Pakistan for the equitable management and distribution of the six rivers of the Indus system. Brokered by the World Bank, the Treaty has endured through decades of political tension, serving both as a technical water-sharing framework and a rare example of sustained bilateral co-operation in South Asia.

Historical and Geopolitical Context

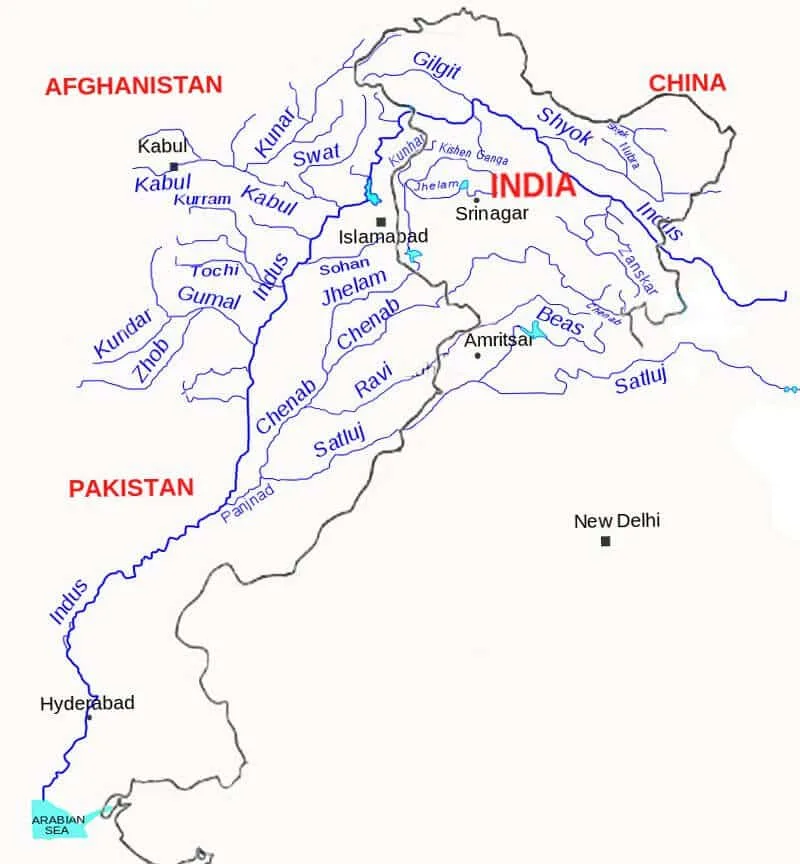

Under British rule, extensive canal systems had been constructed across the Punjab region, drawing upon all six rivers, namely Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej, for irrigation and flood control. These works fostered a densely irrigated agrarian economy that straddled what would become India and Pakistan.

However, the abrupt division of territory in August 1947 left the headworks of most eastern rivers in Indian Punjab, while Pakistan’s new province of West Punjab downstream became heavily reliant on flows beyond its control. Pakistan’s urgent appeals to maintain pre-existing supplies were met by India’s plans for storage and hydroelectric development. However, the bilateral talks between 1948–51 failed to produce a binding arrangement, and in late 1951, both parties accepted the World Bank’s offer to mediate. The Bank’s proposal envisioned a joint Commission, endowed with technical expertise and guided by impartial oversight, to reconcile competing claims and devise a durable settlement.

Negotiation and Signing of the IWT

Following the World Bank’s proposal, each country formed a commission consisting of a Commissioner, supported by engineering and legal teams. The World Bank provided approximately half of the Commission’s operating budget, and its President acted as the final arbiter when the two Commissioners could not agree.

The key issues deliberated by the two commissions were:

- River Allocation: Which rivers should be designated to which country?

- Storage Capacities: What quantum of storage projects could India undertake on the western rivers without materially reducing Pakistan’s flows?

- Technical Constraints: Defining limits on pondage, dam heights and flow controls.

After nearly a decade of exhaustive surveys, data-sharing and draft protocols, President Ayub Khan and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru signed the treaty in Karachi on 19 September 1960. The text was ratified within weeks, and operations began in the New Year.

Terms of the Treaty

According to the IWT, Eastern Rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) were allocated fully to India for unrestricted agricultural, industrial and hydro-electric use. While Western Rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab) were allocated to Pakistan and India may undertake only limited, non-consumptive uses subject to strict technical parameters.

Under the conditions of the treaty, India could build hydroelectric plants without appreciable storage. India was also constrained by maximum pondage and sill levels as set out in Annexures D and E. Further, it was allowed to withdraw water up to 20 per cent of the mean annual flows at any point, for specified purposes.

The Treaty’s nine Annexures and six Schedules detail design criteria for dams, barrages and powerhouses, ensuring that India’s developments will not impede Pakistan’s supplies. These include specifications for (inter alia) maximum pondage volumes, freeboard requirements and flood passage arrangements

Both nations agreed to share real-time hydrological and meteorological data from designated gauge and headworks stations. This transparency underpins flood forecasting, drought management and routine Commission meetings.

Over more than six decades, the IWT has remained a rare beacon of technical co-operation amid a turbulent geopolitical relationship. Its detailed engineering annexures, robust data-sharing provisions and binding dispute-resolution mechanisms have enabled it to endure through wars, regime changes and shifting hydrological realities.

However, the abrupt suspension has drawn concern from key stakeholders, including the World Bank and several UN Member States. Many observers urge both New Delhi and Islamabad to engage the Treaty’s institutional machinery (the Permanent Indus Commission, Neutral Expert and Court of Arbitration) rather than pursue unilateral actions.