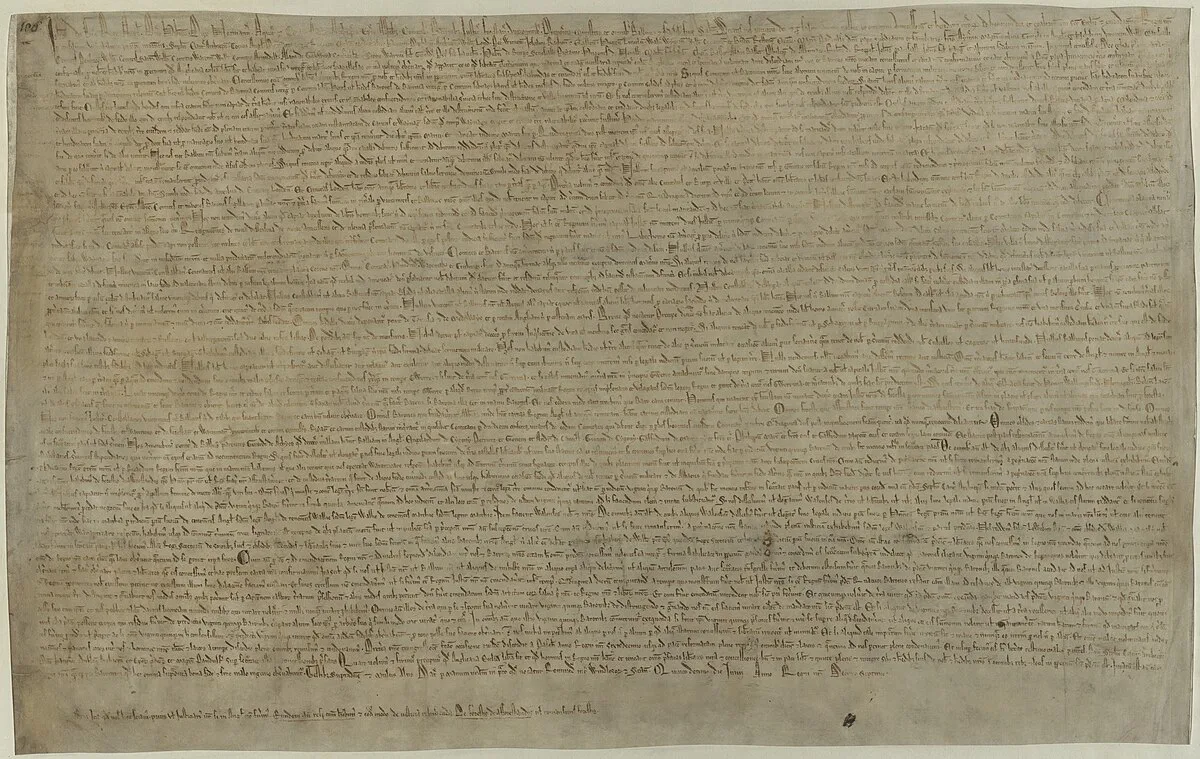

A manuscript long believed to be a 14th-century copy of the Magna Carta held by Harvard Law School has been identified as an original from the year 1300, the final reissue of the historic charter under royal seal. This significant discovery was made by Professor David Carpenter of King’s College London, whose findings, in collaboration with Professor Nicholas Vincent, confirmed the document’s authenticity through advanced imaging and historical research.

In December 2023, Professor David Carpenter, a distinguished scholar of medieval history at King’s College London, was perusing the online archives of Harvard Law School Library when he encountered a curious listing. It was a manuscript described as a 1327 version of the Magna Carta, noted as being “somewhat rubbed and damp-stained.”

Upon examining the digital images more closely, Carpenter made a remarkable observation. The characteristics of the manuscript were strikingly similar to the 1300 Magna Carta, the final version issued under royal authority by King Edward I. According to the BBC, Carpenter recalled his reaction vividly, stating, “What do I see before my eyes? It appeared to be an original of the 1300 Magna Carta.”

The Magna Carta, originally sealed by King John in 1215, is widely regarded as one of the cornerstones of Western legal tradition. It introduced the groundbreaking principle that no person, including the monarch, is above the law. Throughout the subsequent century, successive English sovereigns reissued the charter, with the 1300 version being the last full iteration formally endorsed by the Crown.

Although copies were distributed to counties across England, only 24 originals from the various reissues between 1215 and 1300 are known to survive. Of these, merely six had been verified as dating from 1300 until this recent discovery.

Harvard acquired the manuscript in 1946 for $27.50 (equivalent to approximately $460 today) from a London bookseller. At the time, it was assumed to be a later copy from 1327 and remained largely unnoticed in the university’s law library for decades. That changed when Carpenter, applying his scholarly expertise, recognised its true significance.

He sought the assistance of Professor Nicholas Vincent, an authority on the Magna Carta at the University of East Anglia. Together, they undertook a meticulous comparison between Harvard’s manuscript and the six previously known 1300 originals, examining textual layout, handwriting, and physical characteristics.

Using ultraviolet and spectral imaging techniques, the researchers uncovered critical features that supported their hypothesis. Notably, they identified the elongated capital “E” in “Edwardus” and verified textual elements that precisely matched those in the authenticated 1300 documents.

Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center facilitated the imaging process using advanced multispectral photography equipment. These efforts revealed subtle but decisive evidence.

The scholars then turned to the document’s provenance. Professor Vincent concluded that the manuscript likely originated in Appleby, a now-defunct parliamentary borough in northern England. He proposed a possible lineage of ownership, beginning with the prominent Lowther family, through the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, who may have received it as a gift, and eventually to decorated war veteran Forster Maynard, who sold it in London in 1945.

Harvard purchased the item the following year, as reported by NPR. While definitive documentation of this ownership chain remains elusive, Vincent believes the accumulated evidence linking it to Appleby is highly persuasive. Further archival research may yield concrete verification.

Despite its weathered condition, the newly authenticated Magna Carta holds not only significant monetary value but also immense symbolic importance. A 1297 edition was auctioned in 2007 for $21.3 million, and experts suggest Harvard’s document could be worth a comparable amount. Nonetheless, the university has expressed no intention to sell the manuscript.

Scholars are inspired by its historical and educational impact rather than its financial potential. Amanda Watson, Assistant Dean at Harvard Law School, emphasised that this discovery underscores the essential function of libraries, which is not only preserving cultural artefacts but also facilitating their rediscovery.

Prof. Carpenter described it as “the last Magna Carta” and “one of the most important documents in world constitutional history.”

The original 1215 Magna Carta was written in iron gall ink on parchment, in medieval Latin, and authenticated with the Great Seal of King John. The principles enshrined in the document continue to resonate, particularly in contemporary debates around governance and individual rights.

Professors Carpenter and Vincent are scheduled to visit Harvard in June and anticipate that the document will soon be formally published. The discovery also raises an intriguing question—how many other treasures lie hidden in institutional collections, awaiting a discerning eye?