A graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has introduced a groundbreaking artificial intelligence (AI)-powered method that could significantly alter the field of art restoration. This new approach offers a means of restoring damaged paintings in a matter of hours, in contrast to the traditional process that often requires months of meticulous work.

The method was developed by Alex Kachkine, a mechanical engineering student interested in art conservation. The technique allows for accurate and reversible restoration of artworks, many of which have languished in storage due to the high cost and labour-intensive nature of conventional methods.

“This is a restoration process that saves a great deal of time and money, while also being reversible, which many consider essential to preserving the authenticity of a piece,” Kachkine told Nature.

Conservation professionals often avoid direct retouching of artwork because visible damage is considered a part of the painting’s historical narrative. Ethical guidelines in the field advise that any interventions should be both minimal and reversible. Some institutions have experimented with digital restorations presented alongside the original work, although these alternatives lack the visual and emotional impact of the actual piece seen in full splendour.

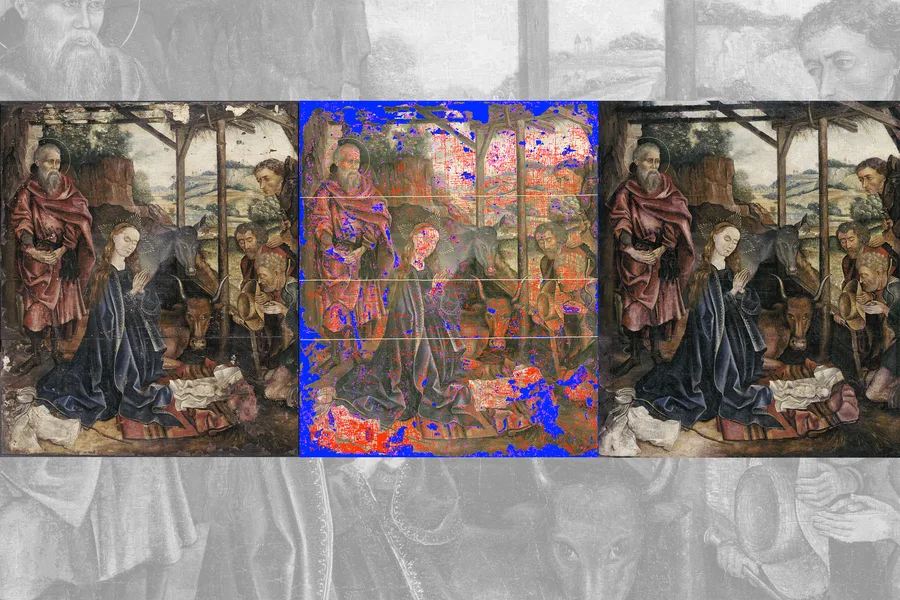

Kachkine’s solution addresses this challenge directly. Using existing AI tools, he generates a digital reconstruction of how the painting might have originally appeared. His software then creates a detailed map that indicates where retouches are needed and specifies the exact colours to be applied. This map is printed onto a double-layered transparent polymer film, one layer containing the coloured retouches and the other a white backing. The film is then affixed to the painting using standard varnish, allowing the retouches to align with damaged areas while preserving visibility of the original work.

“To reproduce colour faithfully, you need both white and coloured ink to achieve the full spectrum,” Kachkine said in an MIT statement. “Any misalignment is highly noticeable, so I developed computational tools based on human colour perception to determine the smallest practical area we can align and restore.”

The process was tested on a heavily damaged 15th-century oil painting by an unknown Dutch artist. The AI-assisted system filled 5,612 damaged regions using over 57,000 unique colours in just three and a half hours. Traditional restoration would likely have taken more than 70 hours for a similar result.

Speaking to The Guardian, Kachkine described the moment of success following years of research and development. “There was a fair bit of relief that this method was finally able to reconstruct and stitch together the surviving parts of the painting,” he said.

Despite its promise, the technique introduces new considerations. Experts question whether AI-generated retouches can truly replicate an artist’s original vision. Others express concerns about the visual impact of the overlay and the long-term effects of varnish on historical materials. Hartmut Kutzke, a chemist at the University of Oslo’s Museum of Cultural History, writing in Nature News and Views, emphasised the need for further research, although he welcomed the reversibility of the method.

Nonetheless, the technology holds significant promise for institutions that lack the resources for traditional conservation. Kachkine concluded in the study that this method offers conservators “greatly increased foresight and flexibility,” and could make it possible to restore countless paintings currently regarded as unworthy of large-scale investment.